Systems of Equations (08-system)¶

So far we have solved single PDEs with a weak formulation

of the form  , where

, where  was a continuous approximation in the

was a continuous approximation in the

space. Hermes can also solve equations whose solutions lie in the spaces

space. Hermes can also solve equations whose solutions lie in the spaces

,

,  or

or  , and one can combine these spaces for PDE systems

arbitrarily.

, and one can combine these spaces for PDE systems

arbitrarily.

General scheme¶

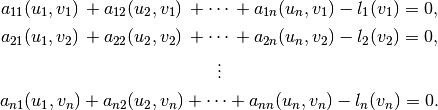

First let us understand how Hermes handles systems of linear PDE whose weak formulation is written as

(1)

The solution  and test functions

and test functions  belong to the space

belong to the space  , where each

, where each  is one of the available function spaces

is one of the available function spaces  ,

,

,

,  or

or  . The resulting discrete matrix problem will have

an

. The resulting discrete matrix problem will have

an  block structure.

block structure.

Model problem of linear elasticity¶

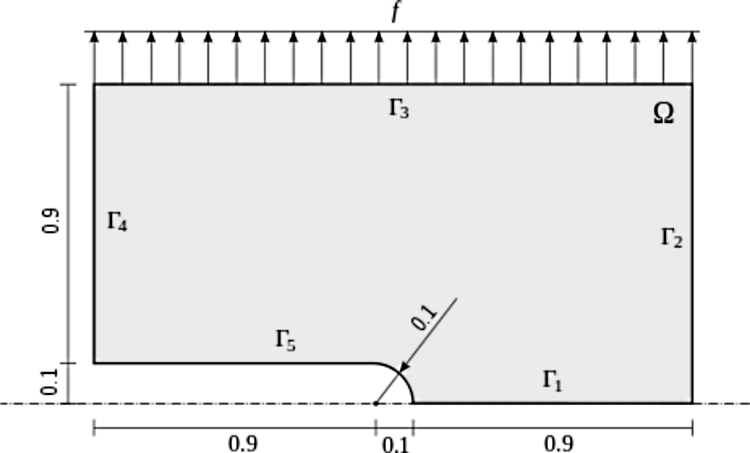

Let us illustrate this by solving a simple problem of linear elasticity. Consider a two-dimensional elastic body shown in the following figure. The lower edge has fixed displacements and the body is loaded with both an external force acting on the upper edge, and volumetric gravity force.

In the plane-strain model of linear elasticity the goal is to determine the

deformation of the elastic body. The deformation is sought as a vector

function  , describing the displacement of each point

, describing the displacement of each point

.

.

Boundary conditions¶

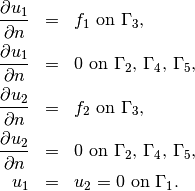

The boundary conditions are

The zero displacements are implemented as follows:

// Initialize boundary conditions.

DefaultEssentialBCConst<double> zero_disp("Bottom", 0.0);

EssentialBCs<double> bcs(&zero_disp);

The surface force is a Neumann boundary conditions that will be incorporated into the weak formulation.

Displacement spaces¶

Next we define function spaces for the two solution

components,  and

and  :

:

// Create x- and y- displacement space using the default H1 shapeset.

H1Space<double> u1_space(&mesh, &bcs, P_INIT);

H1Space<double> u2_space(&mesh, &bcs, P_INIT);

int ndof = Space<double>::get_num_dofs(Hermes::vector<Space<double> *>(&u1_space, &u2_space));

info("ndof = %d", ndof);

Weak formulation¶

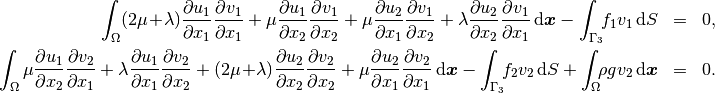

Applying the standard procedure to the elastostatic equilibrium equations, we arrive at the following weak formulation:

(the gravitational acceleration  is considered negative).

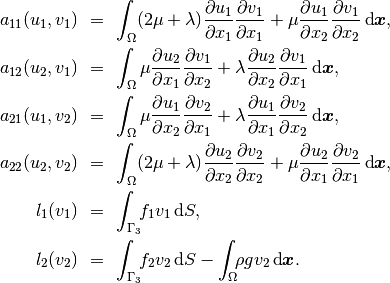

We see that the weak formulation can be written in the form (1):

is considered negative).

We see that the weak formulation can be written in the form (1):

Here,  and

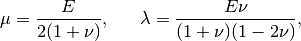

and  are material constants (Lame coefficients) defined as

are material constants (Lame coefficients) defined as

where  is the Young modulus and

is the Young modulus and  the Poisson ratio of the material. For

steel it is

the Poisson ratio of the material. For

steel it is  GPa and

GPa and  . The load force is

. The load force is  N.

N.

Definition of weak forms¶

Hermes provides default Jacobian and residual forms for linear elasticity (see Doxygen documentation). These are volumetric forms that can be used for problems with Dirichlet and/or zero Neumann boundary conditions. The weak formulation for this problem is implemented using those forms (see definitions.h and definitions.cpp).

In the forms, the block index  ,

,  means that the bilinear form takes basis functions from

space

means that the bilinear form takes basis functions from

space  and test functions from space

and test functions from space  . I.e., the block index

0, 1 means that the bilinear form takes basis functions from space 0 (x-displacement space)

and test functions from space 1 (y-displacement space), etc. In this particular case the

Jacobian matrix has a

. I.e., the block index

0, 1 means that the bilinear form takes basis functions from space 0 (x-displacement space)

and test functions from space 1 (y-displacement space), etc. In this particular case the

Jacobian matrix has a  block structure.

block structure.

Flags HERMES_SYM, HERMES_NONSYM, HERMES_ANTISYM¶

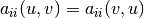

Since the two diagonal forms  and

and  are symmetric, i.e.,

are symmetric, i.e.,

, Hermes can be told to only evaluate half

of the integrals to speed up assembly. This is reflected by the parameter

HERMES_SYM in the constructors of these forms.

, Hermes can be told to only evaluate half

of the integrals to speed up assembly. This is reflected by the parameter

HERMES_SYM in the constructors of these forms.

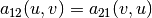

The off-diagonal forms  and

and  are not

(and cannot) be symmetric, since their arguments come from different spaces in general.

However, we can see that

are not

(and cannot) be symmetric, since their arguments come from different spaces in general.

However, we can see that  , i.e., the corresponding blocks

of the local stiffness matrix are transposes of each other. Here, the HERMES_SYM flag

has a different effect: It tells Hermes to take the block of the local stiffness

matrix corresponding to the form

, i.e., the corresponding blocks

of the local stiffness matrix are transposes of each other. Here, the HERMES_SYM flag

has a different effect: It tells Hermes to take the block of the local stiffness

matrix corresponding to the form  , transpose it and copy it where a block

corresponding to

, transpose it and copy it where a block

corresponding to  belongs, without evaluating

belongs, without evaluating  at all. This again

speeds up the matrix assembly. In other words, the form DefaultJacobianElasticity_1_0

is not needed.

at all. This again

speeds up the matrix assembly. In other words, the form DefaultJacobianElasticity_1_0

is not needed.

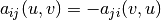

Hermes also provides a flag HERMES_ANTISYM which is analogous to HERMES_SYM but the sign of the

copied block is changed. This flag is useful where  .

.

Even if your weak forms are symmetric, it is recommended to start with the default (and safe) flag HERMES_NONSYM. Once the model works, it can be optimized using the flag HERMES_SYM.

Assembling and solving the discrete problem using Newton’s method¶

When the spaces and weak forms are ready, one can initialize the Newton solver and adjust some parameters if necessary:

// Initialize Newton solver.

NewtonSolver<double> newton(&wf, Hermes::vector<Space<double> *>(&u1_space, &u2_space));

newton.set_verbose_output(true);

newton.set_newton_tol(NEWTON_TOL);

newton.set_newton_max_iter(NEWTON_MAX_ITER);

Next we perform the Newton’s iteration:

// Perform Newton's iteration.

try

{

newton.solve();

}

catch(Hermes::Exceptions::Exception e)

{

e.printMsg();

}

Note that two steps are taken although the problem is linear:

I ndof = 3000

I ---- Newton initial residual norm: 64400

I ---- Newton iter 1, residual norm: 4.52624e-07

I ---- Newton iter 2, residual norm: 9.7264e-09

<< close all views to continue >>

This confirms that using Newton for linear problems is useful. Last, the coefficient vector is translated into two displacement solutions:

// Translate the resulting coefficient vector into the Solution sln.

Solution<double> u1_sln, u2_sln;

Solution<double>::vector_to_solutions(newton.get_sln_vector(), Hermes::vector<const Space<double> *>(&u1_space, &u2_space),

Hermes::vector<Solution<double> *>(&u1_sln, &u2_sln));

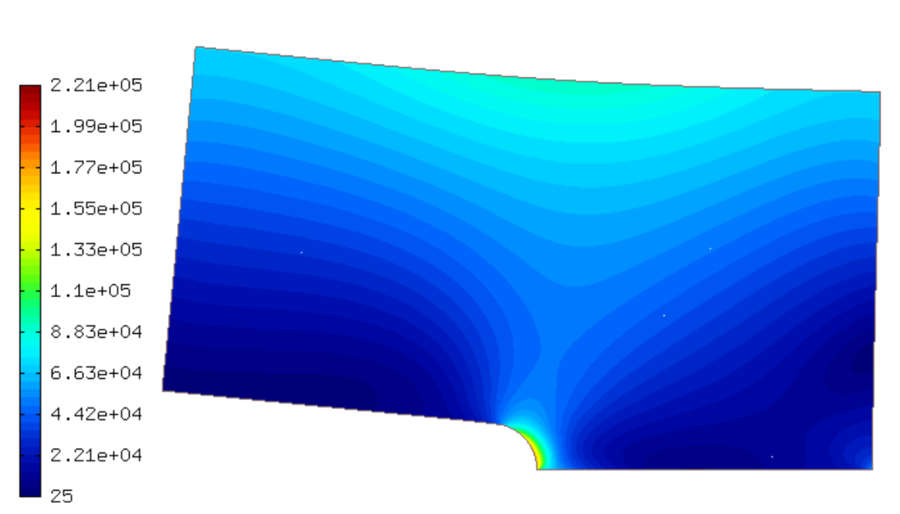

Visualizing the Von Mises stress¶

Hermes implements postprocessing through Filters. Filter is a special class which takes up to three Solutions, performs some computation and in the end acts as another Solution (which can be visualized, passed into another Filter, passed into a weak form, etc.). More advanced usage of Filters will be discussed later.

In elasticity examples we typically use the predefined VonMisesFilter:

// Visualize the solution.

ScalarView view("Von Mises stress [Pa]", new WinGeom(590, 0, 700, 400));

double lambda = (E * nu) / ((1 + nu) * (1 - 2*nu)); // First Lame constant.

double mu = E / (2*(1 + nu)); // Second Lame constant.

VonMisesFilter stress(Hermes::vector<MeshFunction *>(&u1_sln, &u2_sln), lambda, mu);

view.show_mesh(false);

view.show(&stress, HERMES_EPS_HIGH, H2D_FN_VAL_0, &u1_sln, &u2_sln, 1.5e5);

Here the fourth and fifth parameters are the displacement components used to distort the domain geometry, and the sixth parameter is a scaling factor to multiply the displacements.